Required moves to remote locations in oil-field and upstream fields and unintentional biases towards male candidates means that in the case of one industry – oil and gas – many women leave relatively early in their careers, according to a report McKinsey & Company report.

This contributes to the creation of a “hollow middle,” which has profound long-term effects, reducing the number of women available for promotion.

“As a result, women can never catch up and remain even more underrepresented throughout the pipeline,” said the report.

But the study highlights some telling factors in the recruitment process that is impacting so many more business sectors than oil and gas (O&G).

Therefore, the problem of untapped female talent is not unique to O&G, however, but it is “more acute”, said the report.

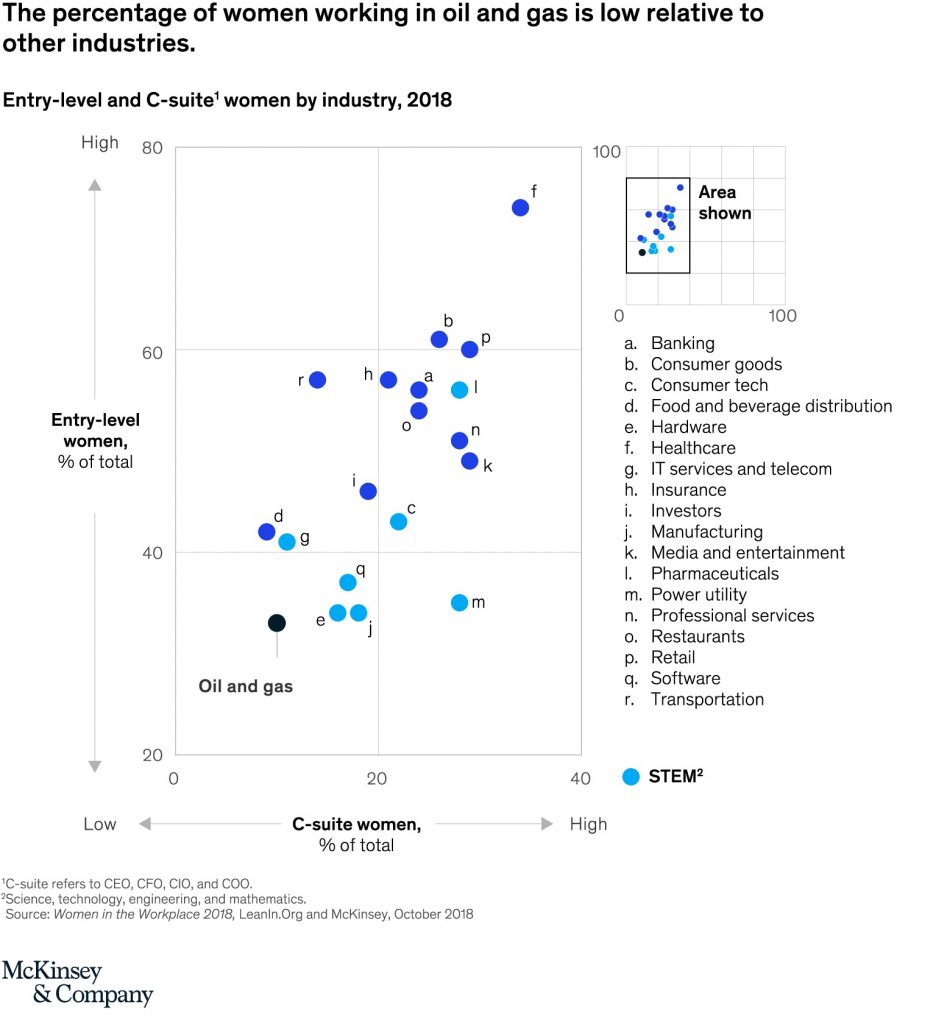

When compared with 18 other industries, O&G was last in female participation at entry-level and second to last in the C-suite (Exhibit 2). When compared with other science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) industries, it ranked last.

One executive that participated in the research noticed that a list of “high potentials” in their company had notably few women on it. Curious as to why their team looked at the relevant performance reviews and found that women in equivalent positions to those in the high-potential group also had similar performance records.

Why, then, were these women not considered “high potential”? The answer, according to the report, was that they had “mistakenly been overlooked”.

If excellent female candidates are overlooked at every subsequent stage of the O&G pipeline, the percentage of women sequentially declines, and at faster rates than in other industries.

Julia Sperling, a McKinsey health and science Partner specialising in the Middle East, who is also a medical doctor with a background in neuroscience, explains in this video below the unconscious biases towards perceived or actual female characteristics and one’s perception of ‘leader’ characteristics. This is called a double-bind situation.

The conflict of bias will often impede the recruitment selection process for female candidates, regardless of their track records and skillsets.

McKinsey indicates that there are two main hurdles for women in O&G—getting the first promotion into management and then getting promoted at the senior vice-president (SVP) level.

One area of O&G that could be unnecessarily be putting a spanner in the works of female promotion relates to the common expectation that it is necessary to accept international or remote assignments to get promoted.

“That can be challenging for those starting or raising young families at this point in their careers,” noted the report.

One CEO interviewed highlighted that the centres of O&G operations are often in remote or otherwise unappealing places. But passing up such opportunities early in their careers “worsens women’s chances of promotion later.”

Men, of course, can face the same issue, but based on our experience and after discussions with O&G leaders, McKinsey researchers found that it affects women more, hurting their relative representation.

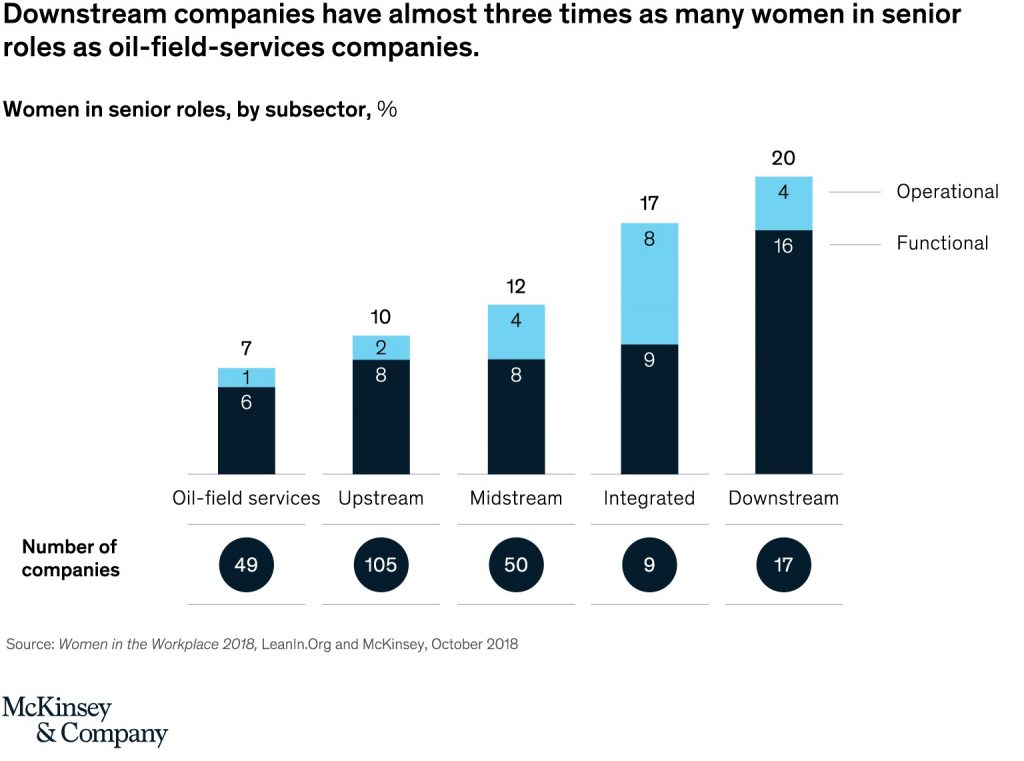

Of the 250 North American O&G companies surveyed, the percentage of women in top roles—meaning at the vice president, senior vice president, and C-suite levels—varied significantly, depending on the subsector.

“Executive-level female representation in integrated exploration and production (E&P) companies (including majors and other companies integrated downstream) and downstream-only companies are two to three times higher than in oil-field services and upstream companies,” said the report.

How visibility can lead to promotability: Stepping into the Spotlight

However, with similar trends of good performing female candidates also largely appearing to be overlooked in other industries, the pattern across the senior management career chain is remarkable and unnerving.

This flawed hiring pattern has an impact not only within the potential success of any one company but the greater economy. For every female candidate overlooked, is a family’s purchasing power suppressed.

To put this in perspective, research by The Institute for Women’s Policy Research said that equal pay would add an additional income of $512.6bn to the US economy if men’s wages stayed the same.

If visibility is a major stumbling block for females, a Harvard Business Review Women at Work podcast discussion with Muriel Maignan Wilkins, a managing partner and co-founder of the executive coaching firm Paravis Partners, and others, including Stanford University researcher, Swethaa Ballakrishnen, provides some solutions for women trying to navigate the workplace for greater visibility.

Maignan Watkins retells a story of how visibility early on in her career had to deal with not necessarily putting herself in the spotlight, but creating a spotlight for teams to shine. One-on-one relationships with her boss or those more senior, was invaluable because as she gained influence in the organization, visibility was much more about bringing other people into the spotlight.

“And the more I could share that spotlight with my peers, actually, that’s what gave me traction to be able to get things on board, to get things moving,” she says.

“And then it expanded to my team, and then it expanded to others. And fast forward to now, where I have my own business, it’s not even about visibility on me. It’s visibility about my team, my clients, my partners and the community, and that in retrospect, then shines the light back on me. So, it becomes a very reciprocal relationship,” says Maignan Watkins.

She explains further in the podcast that you need to be thinking about how visibility will benefit not just yourself but others, too.

Ask yourself: why am I doing it?

“There has to be a purpose behind it. And I think that’s especially important for women because we tend to be more purpose-driven, that there is a purpose even larger than us as to why we want to be visible.”

Maignan Watkins

Preparation is key to getting your objectives across clearly so that others understand it. This is paramount in a meeting that you want to present an idea and how it will benefit the team, etc. Do not wing it. Make sure you have three concise points to present.

And make sure you have your target manager in mind to present your project milestones to as and when they happen. Waiting until a project is over is too late. Present progress and wins along the way, this illustrates momentum and visibility.

Taking the guessing out of aggressive

Ballakrishnen explains that women in the study thought the dominant leadership style was assertive. It was individualistic. It was very self-promoting. “And they didn’t see themselves as being that sort of leader.”

The second factor was women found being assertive meant as being not authentic to who they really are.

“Women felt like when they were aggressive, when they did take on these roles of individualistic, self-promoting selves, there was a backlash because that doesn’t reconcile with the expectations of feminine norms that they are attached to.”

-Swethaa Ballakrishnen

The researcher explains further that taking the typical road to visibility did not gel as the women had families and responsibilities not just at work, but were also balancing incredible pressure from partners to make specific choices about their careers.

Being authentic = Your Comfort Zone

Maignan Watkins highlights with her clients how to be authentic regardless of the team or work situation you are in. The way to become authentic is to “maximize the things that make you comfortable:

She suggests that you start thinking about what makes you comfortable, that’s truer to who you are, then you can start thinking about the conditions that actually will increase the probability that you will work on their visibility.

“So it’s never about being inauthentic; it’s about finding ways that make it comfortable for you,” says Maignan Watkins.

To have a listen to the HBR podcast, click here

Own the Room: Discover Your Signature Voice to Master Your Leadership Presence, by Amy Jen Su and Muriel Maignan Wilkins, can be purchased here

How women can help fill the oil and gas industry’s talent gap, October 2019, McKinsey & Company, www.mckinsey.com. Copyright (c) 2019 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.